A History

of Don Public Theatre

Acting as the secret conscience of the Cleveland independent theatre scene of the 1990s was the performance of a lifetime.

By Rodney E. Griffith

The atrium was bubbling with an afterparty, a post-performance gathering.

I had not been invited. My appearance was as an impromptu guest of an associate who was in the midst of staging a show at another venue, Cleveland Public Theatre. Befitting the customarily ramshackle nature of the Cleveland indie Theatre scene in the early 1990s, hors d’oeuvres were nowhere to be found and the beverage on hand was orange Kool-Aid.

In spite of my low-key self-image, a cranky bohemian woman immediately zeroed in on me. It was like a clichéd airport scene with an aggressive Hare Krishna. “Lose the tie,” she demanded in a grating, nicotine-encrusted voice. “Lose the coat. What are you, rich?”

I was not. At the time I was barely skating above the lowest of legal compensations on the bottom rung of the design ladder. In spite of the woman’s reputation as an outsider artiste, she wasn’t intentionally being ironic. I was skeptical that irony was even on her palette. I demurred and politely refrained from mentioning the grant money she had recently received to broadcast a decidedly noninclusive POV to her dozens of viewers. I was attempting to publish a zine in the latter days of the boom and could have, in my less than humble estimation, put the money to better use. I would have at least offered drinks.

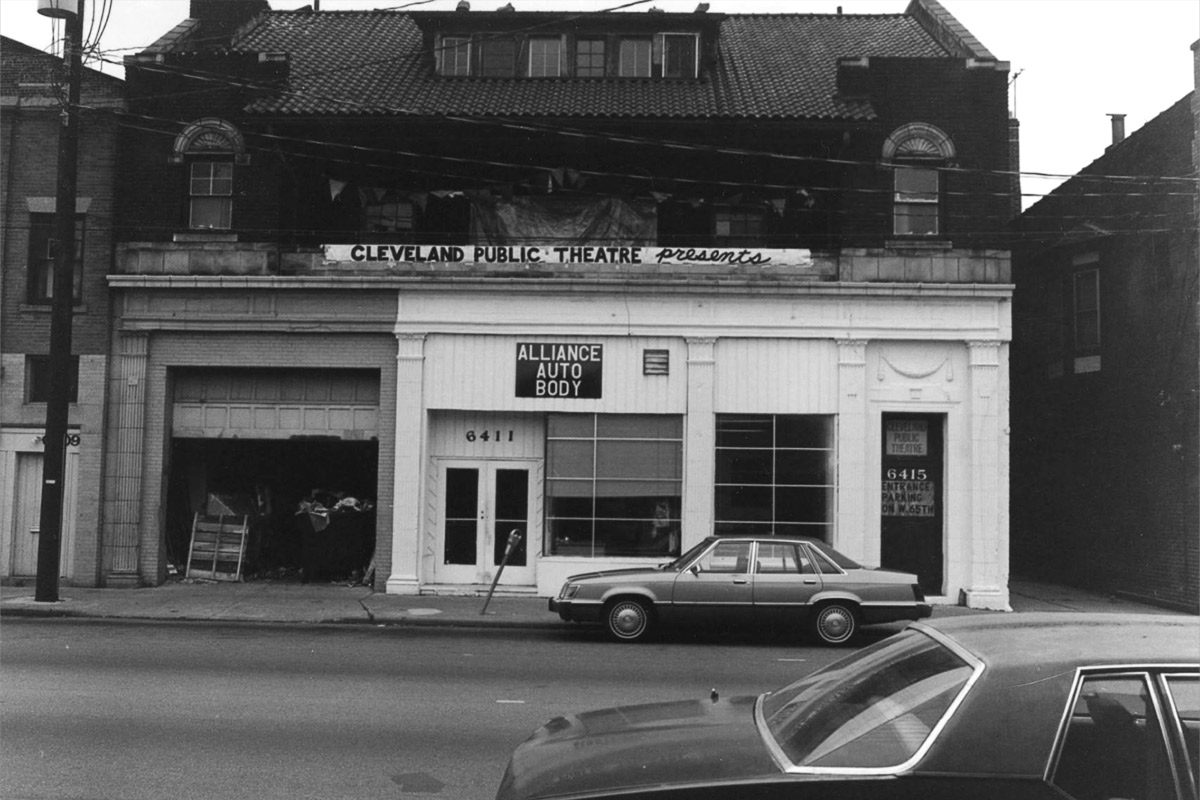

This is not Don Public Theatre. The original CPT storefront circa 1991. Courtesy Cleveland Public Library Photograph Collection.

Cleveland Public Theatre had been founded some ten years earlier by local attorney James Levin, whose efforts and investments in redeveloping a blighted West Side neighbourhood cannot be understated. The theater he established infused a largely derelict part of Cleveland’s west side with the breath of culture and today the results of said efforts are evident. Those early days, however, were rough and looked it. (Extra excitement was provided by the adjacent parking area, where the odds of one’s car being present and intact at the end of a performance were less than reassuring.) Although the upper/main floor of 6415 Detroit Avenue was the designated space for its main features, the associate had been consigned to the “downstage” (read: basement). This was by no means an impediment. On a visual basis the lack of natural light and the abandoned character of the building enabled a built-in dramatic atmosphere. The space held much promise to be CPT’s 72 Whooping Cough Lane, but as with much regarding CPT, this was a promise never to be seen, let alone capitalized on. In spite of some of its cause célèbre performances CPT always played it straight, even when the material was something like Aubrey Wertheim’s “Make Way for Dyklings”, a two-hander, as it were, set in a bowling alley.

The “Public” face of CPT had seemed something of a misnomer. The main qualifier for Public Theatre was its affordability, access, and ostensibly its sense of inclusion, but that only spoke to potential, not the actual breadth of offerings. It was not a venture on a plane with Public Broadcasting, which offered content like The Goodies and rafts of educational programs, including in its recent past more than a few scarring drama anthologies. To all appearances, CPT served a chosen sliver of its potential audience; as late as 2011, many years outside the scope of this retrospective, Scene was calling out CPT participants for resembling “doubles for the cast of Glee.”

Attending the then-in-residence annual Performance Art Festival (a mixture of straight standup, involuntary puppetry and carnival mimes) was like having messages in plastic bottles thrust at you. Yes, see, it’s clever, we’ve hidden subtext, the devalued Cracker Jack surprise that was barely more substantial than its wrapping. When watching any CPT production, what struck me again and again was the disconnect between the artistes and any established culture outside their own comfort zone. When introduced to a performance art group calling themselves Primus Theatre, one had the uncomfortable sense that they were obstinately unaware of the Les Claypool-led group, then in frequent rotation on a pre-16 and Pregnant MTV and local radio (including Cleveland’s self-aggrandizing alt-rock station, WENZ). A Lenny Bruce tribute was as close as the early CPT veered toward approaching the milieu that would have been most receptive to its overall mission, but the idea of an equivalent contemporary or non-ghostly voice seemed unimaginable (I am reasonably sure Bill Hicks never attended a CPT performance). As a member of the audience I would find myself momentarily amused and occasionally touched by some creative spark, only to be disappointed as it quickly extinguished in a dark puddle of ungiving ideology.

Apart from the open-door policy, I was never entirely sure what the associate was doing there, either. At the same time he was appearing in CPT productions, he was an unabashed consumer of the mainstream. He had a Frenchman’s devotion to comedic performances on garbage sitcoms, once offering me an appreciation of the two main actors in Perfect Strangers, a television series interchangeable with a hundred other American network comedies. He was a devotee of pseudo-auteur John Hughes and 1980s horror films. (As more of a Hammer person, we didn’t bond over these, either; while in attendance for an advance screening of one of the Hellraiser films, it struck me that the script reused the exact resolution of “One Froggy Evening” but took two hours to get there.) I wrote a premise that was the perfect consummation of this dichotomy, “Bunraku Alf” in which the 1980s alien committed an act of seppuku (“Ah! I kill me!”). The associate then lifted the bit in its entirety for a one-man performance piece, even constructing his own shrouded Alf puppet (with miniature short sword), but the joke fell predictably flat on the audience. In 1994, he staged a production that was a hybrid Ultraman/Rankin-Bass/Sid and Marty Krofft Christmas extravaganza. (It was for The Battle for Christmas that I received my sole CPT credits, as Light and Sound Operator and Program Designer, which I have neglected to add to my LinkedIn profile.) No fan of ad libbing, when one of his actors blew a punchline, he recorded the entirety of the show’s dialogue, added music and sound effects, and dubbed it to a VHS cassette, instructing the cast to lipsync badly. It was exactly the shot of fun-with-no-purpose that Cleveland Public Theatre badly needed, but there should have been a third option all along, one that would have run in the direction of antecedents like Private Eye and The Firesign Theatre, one that would have questioned the sometimes dodgy intent of the theatre, its participants, and especially its audience. Levin came of age in the 1960s and believed in the potential for stage performance to communicate, so it was not unreasonable to expect an epiphanic moment that transcended the practical. If that moment ever came, CPT neglected to send me comped tickets.

Fortunately, the associate had been christened “Donovan Théâtre” at birth, so adding “Public” in the middle was a natural.

Originally in the form of a very cheap birthday card in 8 page minicomic format (typed on the reverse of the envelope: “When you care enough to send the very worst”), the original Don Public Theatre “schedule” This Is Don Public Theatre japed CPT and the eponymous Mr. Théâtre while establishing the imaginary venue—theatre of the mind at its purest—as a kind of wickedly creative Shangri-La. It also inaugurated a tradition of including local personalities and obscure professionals that only made conversational sense at the time, i.e. Kim Richards decades before she became a reality housewife-cum-homicide suspect and Malachi Throne. (The arbitrary nature of these namechecks persisted throughout the project.) Once posted, I had almost forgotten the schedule’s existence until, days later, “Don” walked into my place of employment, intoning his single word reaction: “Genius.” I accepted with some modesty, given the wages I was pulling there, but the enthusiastic response made an impression. One and done was not to be.

DPT schedules began circulating through the mail (instantly a hundredfold circulation increase). Borrowing from the 1980s punk/anarcho-libertarian/mail art sensibility of zines, the barbedness of 1960s newsletters, and especially the conciseness of small press comics, DPT had a unique selling proposition in that it was one joke serving as an umbrella concept, and one that always looked the part. On top of every other sin they’d committed, the crude appearance of much of CPT’s print collateral rankled; even taking into account the modest promotional budgets involved, there was simply no excuse for the poor impression they made. The visual style of DPT, although presented in scale, towered over CPT’s.

The Don Public Theatre project became too fun to stop and thus began an irregular habit of DPT minis chiding CPT’s not-infrequent pleas for attention and financial contributions, which lacked in subtlety even when compared to the DPT parody version, “Why We Need Your Money”. The sometimes brazen lack of creativity and self-awareness from CPT talent begged to be documented. One such show, ridiculed in DPT Presents Fraudeville as “Performance Art Match Game”, solicited audience input before curtain. I filled out several “audience participation” cards containing unfinished lines such as “When I touch my [blank], I feel [blank].” I dashed off “When I touch my temples, I feel religious” and other sharpish gems. They used four or five. I felt like I’d written more of the show than they had.

DPT Presents Fraudeville continued the trajectory of a shooting gallery where no targets were spared. The aforementioned “Make Way for Dyklings” became a more succinctly-named story which, save for its blunt parody title, forwent any sexual identity politics in favour of calling out the frowned-upon societal inclination of bowling. Contemporaneously the actual Don was self-publishing a “personalzine,” a print format very much a forerunner of the original weblogs. (He briefly tried transitioning to an online version in the Geocities days, but abandoned it entirely, anticipating the trend of abandoning blogs.) The zine itself was sent up, condensing his endless documented shopping trips as a phoney one-man reading entitled Expense Report, but it only seemed appropriate to follow his cultural diary style on a subsequent undertaking: a non-CPT production by a local college group was commemorated as a program parody, Who Are the Virtual Gods? It should be taken as self-evident that the thespians were trying, as in a grammar school production, their hardest, but holding them to a higher standard seemed somehow fair—and funnier.

“Don Public Theatre is not a comfortable place to perform, because the questions they pose make it dangerous for the actor as well…Nobody leaves feeling unprovoked. I just hope they arrive unarmed.”

—name withheld

Even Don’s actual one man show (itself recycled from the ashes of Mach I of the Christmas show) became a fictional DPT event in which fans were given the exclusive opportunity to spring real money on items such as a CD-ROM diary that included voice samples and the phone numbers of the people he was talking about integrated with dialing software “so you can call them up and play Don’s voice saying bad things about them.” (An app of this nature would today sell in the millions.)

The last of the original DPT minis, the 1995-96 Schedule, was the project’s crowning achievement, a straight parody of the accompanying CPT season listings. Creativity and honesty were often improved by a simple twist on the existing CPT blurbs, like a borrowed quote from a glowing review of a mediocre production: “Everything public theatre should be: subversive, personal, stimulating, a little scary, and cheap.” (Even the clip art Pan used as an early CPT logo was liberated and remixed as the DPT mascot, Pander.) Borrowing SCTV’s model of low concept/high execution (and with more than a nod to John Ewing’s concise and entertaining Cleveland Cinematheque calendar blurbs), omnipresent films of the time became DPT productions like Free Will (in which a giant fish coerces adults into a ridiculous plot to kowtow to their children’s unsophisticated viewing obsessions); a bad experience at a local cinema became the basis for The Pun-Usher. Also on offer were a Real World parody when The Real World and reality television were barely a nascent thing and Crack Troop!, a reimagining of a dopey 1960s TV comedy as a “dope-y” modern western political drama.

One entry spoofed a pre-Vagina Monologues Eve Ensler (“Eve is widely published and promotes AIDS, feminism, and war,” only a syllable away from the actual copy and maybe closer to the truth) while an actress who had previously starred in the Battle for Christmas show was judiciously requoted on the back cover: when she said “Nobody leaves feeling unprovoked” in describing the upcoming Cleveland Public Theatre season, I added the concluding thought, “I just hope they arrive unarmed” for its DPT doppelgänger. For this, I was cast by her as Don’s “mean friend” and this marked the end of my dalliance, such as it was, with CPT. (It probably did not help matters that 1995-96 Schedule was distributed openly at CPT’s snack bar.) I moved on to safer parking, and I have not been challenged at a party since.

1 WENZ-FM, stylized as “The End 107.9”, suffered from similar tunnel vision. A staff member made a dismissive on-air reference to Aretha Franklin as “some Motown (sic) singer” and later waxed rhapsodically about a post-Natalie Merchant 10,000 Maniacs recording, specifically praising the quality of the songwriting, oblivious that the record was a cover of the Roxy Music hit “More Than This”, which had been ubiquitous on local classic rock and Top 40 radio. At the same time, FM college station WCSB and AM stations WWWE and WERE were hosting free-for-all shows by Rick “Gilly” Gilmour, Steve Wainstead, Steve Church et al that would have provided a much more fluid model for CPT than what passed for “alternative” culture.

©2022 Rodney E. Griffith. All rights reserved.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

React